Remote and starkly beautiful, Hovenweep preserves a brief chapter of Ancestral Puebloan history. Sage covers the plains to hide 20 square miles of farms and fields cultivated by early inhabitants; rubble and rock falls now disguise much of their first homes. Surviving though are six groupings of high towers, dating from the mid-thirteenth century. They stand like sentries on canyon rims guarding precious spring waters.

The canyon and mesa country north of the San Juan River holds many archeological sites where ancestors of today's Pueblo Indian tribes lived. Round, square, and D-shaped towers grouped at canyon heads most visibly mark once-thriving communities. No one has lived in them for over 700 years, but they are still inspiring. As today's visitors explore Hovenweep, they often wonder why these towers were built and what sort of communities their builders created.

Many dwellings stood right on the canyon rim, and some structures were built atop isolated or irregular boulders--not practical sites for safety and access. Most are associated with springs and seeps near canyon heads. Such locations suggest that the ancestral Pueblo people were protecting something, if not themselves then perhaps the water--extremely valuable to desert-dwelling agriculturalists. By the 1200s the population had grown dramatically, and pollen studies show that much of the tree cover had been removed. Perhaps drought and depleted resources figured prominently in the ancestral Pueblo peoples' sudden departure in the late 1200s. While many questions remain unanswwered, continuing archeological studies improve our understanding of ancestral Pueblo culture.

W.D. Huntington first reported these structures after he led an 1854 Mormon expedition into southeastern Utah Pioneering photographer William Henry Jackson in 1874 first used the "Hovenweep," which is Ute/Paiute for "deserted valley." When J.W. Fewkes surveyed the area for the Smithsonian Institution in 1917-18 he recommended the structures be protected. Finally, in 1923 President Warren G Harding proclaimed Hovenweep a national monument.

Today tall towers, outlines of multi-room pueblos, tumbled piles of shaped stone, small cliff dwellings, pottery sherds, and rock art lie scattered across the canyon landscape leaving little doubt that a sizeable population once lived in this ruggedly beautiful, high desert setting. Despite seven centuries of weathering, many large structures and tall tower walls still stand as triubutes to their builders. The intricate stonework crafted by these ancestral Pueblo masons is also revealed in the finely hewn stones, sharp corners, and smooth curves of Hovenweep's architecture. Rubble mounds show that even more structures were once significant parts of these villages.

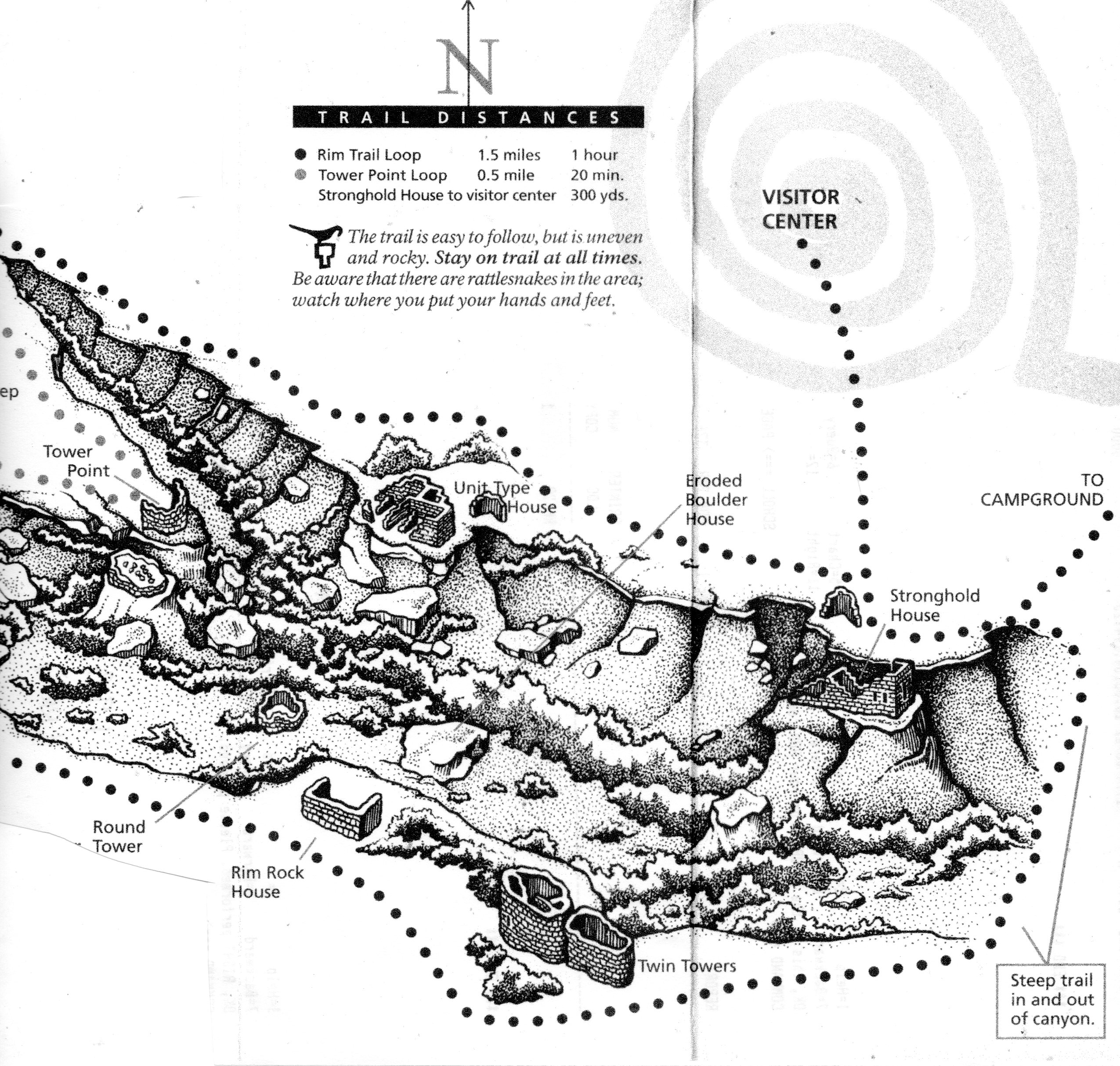

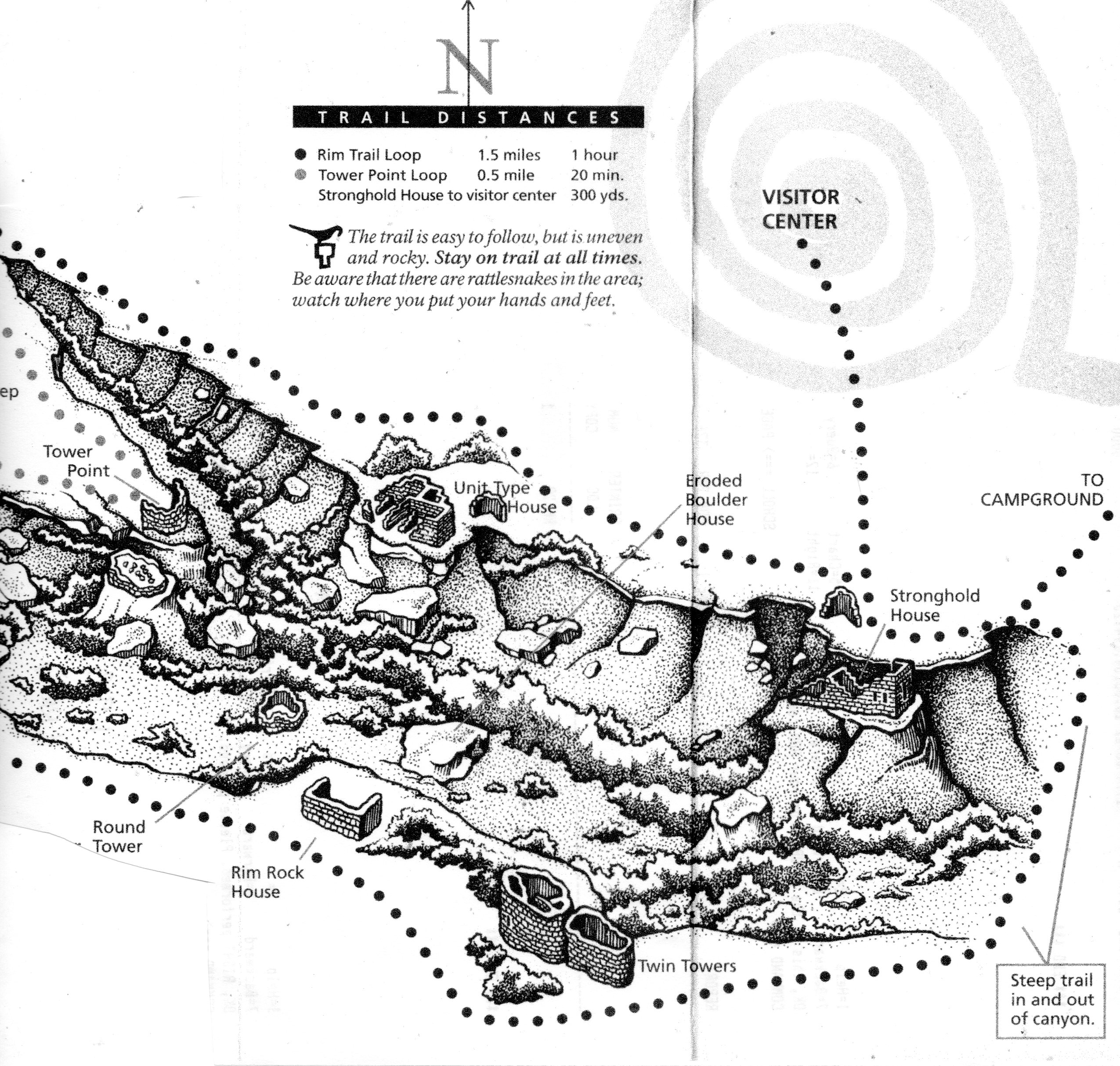

Visitors can walk along quiet, primitive trails and imagine what these communities must have been like long ago when hundreds if not thousands of people lived on this mesa. Hovenweep is truly a place to ponder the past.

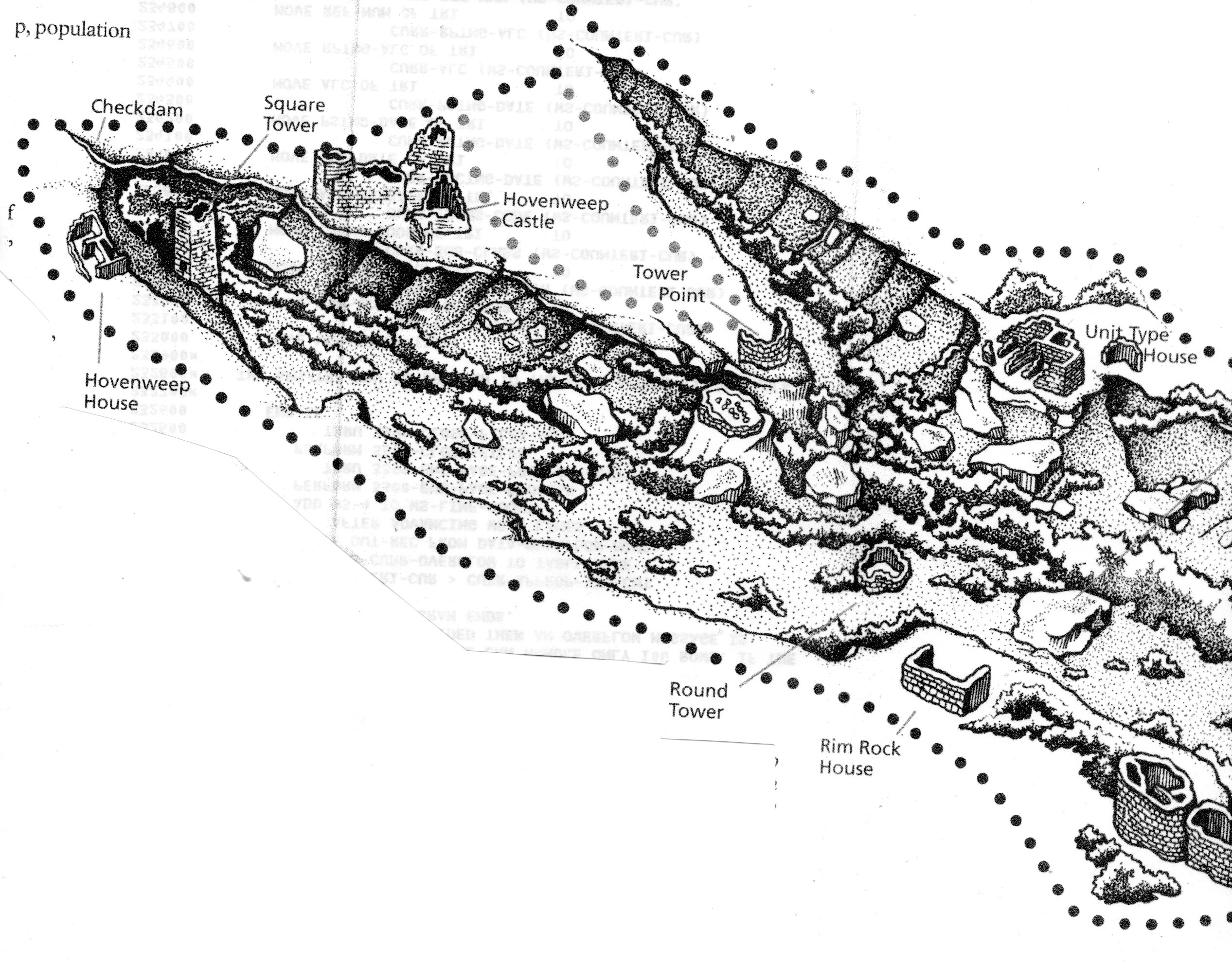

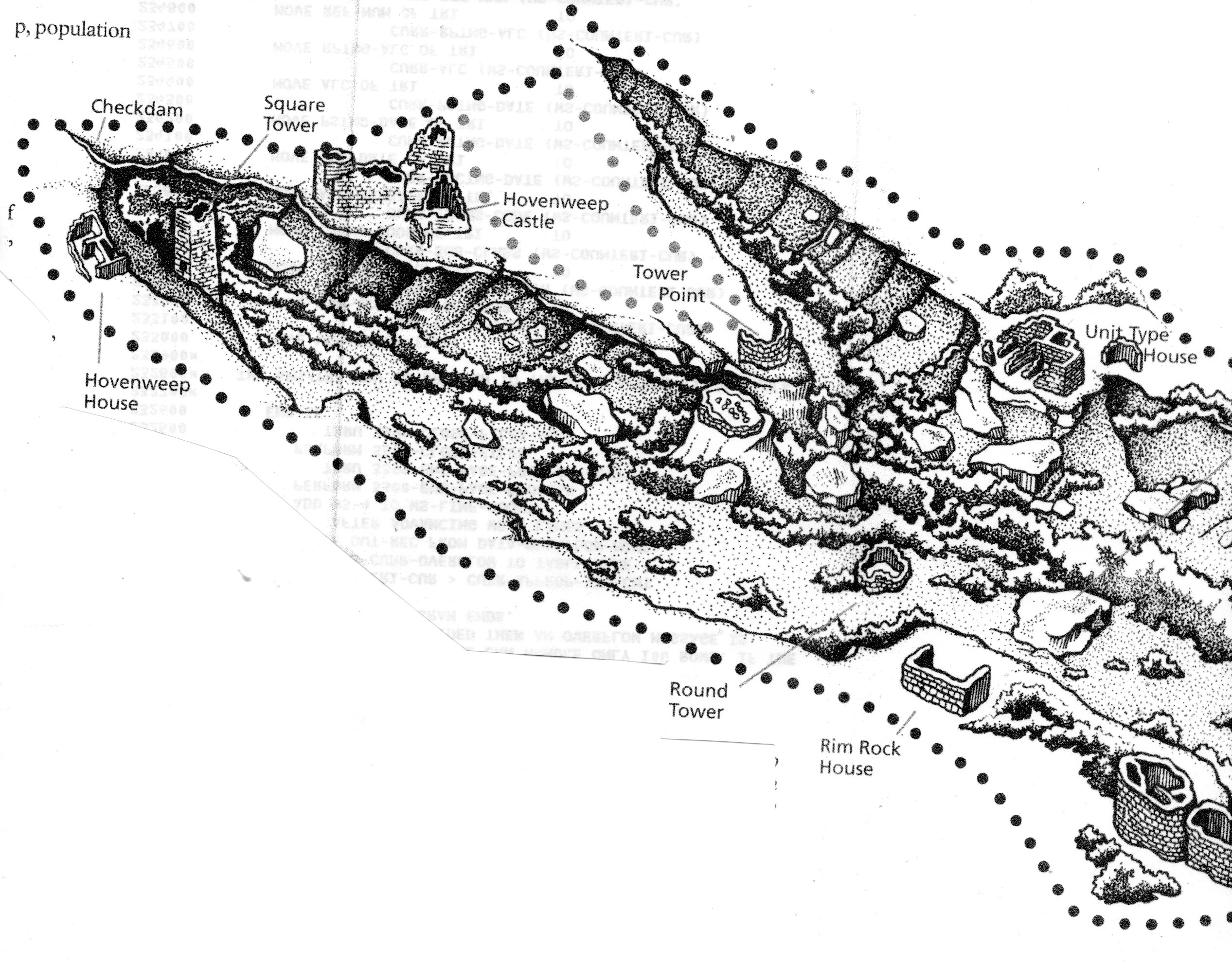

Hovenweep National Monument includes five prehistoric Puebloan-era villages, each located at the head of a separate canyon within 16 miles of each other along the Utah-Colorado border. The Square Tower Unit is the monument's primary contact facility with ranger guided tours, a visitor center, and campground. Outlying units include Holly, Horseshoe , Hackberry, Cutthroat Castle, and Cajon.

The Holly, Horseshoe and Hackberry Units are located about four miles northeast of Square Tower. Cutthroat Castle is about eight miles northeast of Square Tower and Cajon is about nine miles southwest. Each site has a short walking trail along its canyon rim. A four to five mile-long pedestrian trail connects Square Tower to the Holly and Hackberry Units , providing a scenic backcountry hike.

Hovenweep National Monument and its oulying sites are located on Cajon Mesa. This area is defined by intermittent drainages, deeply-cut sandstone ridges, small canyons with seeps and springs, boulder fields, and canyon bottom lands. Plant communities include pinon-juniper woodlands and desert shrublands.

Prior to A.D. 1150, Cajon Mesa witnessed a growing Puebloan population with intensive agriculture. By about A.D. 125, the region appears to have exprienced a population decrease, and villages began to concentrate in and around the headwaters of canyons. This was the start of what archeologistS believe was a period of increasing aridity that included a 23-year drought starting in A.D. 1276

Apparently in response to these conditions, Puebloan communities began building the tower-like structures that are visible today. The towers appear to have been constructed between A.D. 1235 and 21240, and were inhabited for no more than 70 years. By A.D. 1300, Puebloan people throughout the region, including Hovenweep and Mesa Verde, had departed, migrating to southern Arizona and New Mexico.

The standing architecture of southeast Utah was first recorded by Euroamericans of the Mormon expedition in the early 1850s. Hovenweep National Monument was established on March 2, 1923 by President Warren G. Harding.

The standing architecture of Hovenweep was built approximately 800 years ago by ancestors of today's Puebloan people. The masonry found at Hovenweep is very distinctive and shows considerable skill in construction techniques.

Hovenweep National Monument straddles the Colorado-Utah border and was inhabited at least since the beginning of the modern era by people closely related to the Mesa Verde population. By the year 1200 large mesa-top pueblos were abandoned in favor of smaller dwellings scattered at the heads of small canyons, presumably to take advantage of permanent springs to be found there. In comparison to the dwellings at Mesa Verde and Chaco Canyon, buildings at Hovenweep have a marked fortress-like appearance. They are often tower-shaped, with only small openings (or "ports") in place of exterior windows or doors, and tend to be perched rather spectacularly on large boulders or right against the canyon edges.

At one time, this rocky, rugged, open country was home to many people. For thousands of years, people hunted animals and gathered plants, moving on an annual round from the high mesas to the low canyonlands. As corn, or maize, gradually made its way north from Mexico, they became farmers and settled in villages. Along with corn, they grew beans, squash, and a grain called amaranth. There is also evidence they grew cotton.

At Hovenweep, population density varied through time. In the 1200s, increasing numbers of people concentrated at the heads of small canyons, where they built pithouses, pueblos, ceremonial rooms, or kivas, and the towers that are Hovenweep's trademark. Most of the buildings still standing were constructed from A.D. 1230 to 1275, about the same time as the famous cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde. The stunning Square Tower and an intriguing collection of buildings are clustered along Little Ruin Canyon. But the Square Tower community was not alone. Seven hundred years ago, a lively system of settlements flourished in the immediate area, all within a day's walk of each other.

The Square Tower group is located inthe heart of a 500-square-mile raised block of land called Cajon Mesa and is part of the Great Sage Plain. Several streams drain the mesa and flow into the San Juan river to the south

Pioneer photographer William Henry Jackson, who came here in 1874, called this place Hovenweep. It is a Ute/Paiute word that means deserted valley. The fine state of preservation of the structures and their unusual architecture led to Hovenweep's designation as a national monument in 1923.

Hovenweep House

Archeological studies across the Four Corners region have produced intriguing information about past cultures inhabiting this part of the Southwest. Over 13,000 years ago nomadic Paleo-Indian hunters roamed the plateaus and canyons hunting wild animals. Drier climate conditions displaced these people--as larger animals moved elsewhere--and ushered in Archaic hunter-gatherers from the west about 11,000 years ago.

HOME PAGE

Comments?